I revealed myself to those who did not ask for me;

I was found by those who did not seek me

To a nation that did not call on my name,

I said, ‘Here am I, here am I.’…

—Isaiah 65:1

1

The first time he sees her face, the first time he looks into her eyes, the first time he feels her arms around him and his around her, his water will break, and he will wail three decades and three years of tears.

And time will stand still.

2

And it came to pass on the twenty-seventh day of April in the nineteen hundred and sixty-ninth year that Craig Von Hickman went permanently to the home of Hazelle and Mary Juanita Hickman on Thirteenth Street in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was sixteen months of age.

He grew up fast. Way too fast according to Mary Juanita.

In elementary and high school, although many suspected it, and Craig did very little to hide it, no one really knew the truth about him, about him and the boys, about him and Juneau Park, about him and his savior Seldon called Roy.

Oh yes, many knew that he was adopted. That was no secret. And yes, anyone could see he was black. That was no secret either. But no one knew that other truth about him, not his girlfriends, not his would-be girlfriends, not his wannabe girlfriends.

Only his dear friend Joseph the Swimmer knew the truth. Or, perhaps, they all knew the truth, but only Joseph accepted it. Whatever the case, Joseph was the only person to whom he actually told the truth. And though Joseph knew the name Mary and Hazelle had given Craig, Joseph called him Craig van den Landenberg, a name with a bit of Dutch in it.

3On April 16, 1993, Craig’s alter ego and stage persona was born. And he called her April Marie Lynette Jones, but he didn’t know why, and she was a hairdresser who worked in J’s His and Hers Salon, but he didn’t know why, and she appeared wise, and seemed to give great advice, and talked about how everyone else could fix their lives, but she had some deep, mysterious, unspoken pain inside her. And he didn’t know what it was all about, and he didn’t ask her, and she didn’t tell him.

4

On April 16, 1996, he went to see the film secrets and lies at the Kendall Square Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When he saw how the black woman in the movie sought and found her birth mother, a white woman, he could hardly stay seated. Could hardly contain the rumblings and tremors and trembling within, signifying a great internal quake. He knew his earth was about to open for all those around to see, and for this, he was not ready.

When the film ended, Craig left the theater and went home. There he allowed a bit of earth to break, but not too much, for he was not ready.

For the next two weeks, he would lie on the floor of his apartment, in the fetal position, unable to function—yearning, longing, waiting, hoping for the day when his eyes would be opened.

“You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart,” God had said, and so he did. His beloved friends and roommates, Darlin the Musician and Gail the Writer, picked him up off the floor and held him.

And so it was that they began walking with him on his journey toward the light.

5

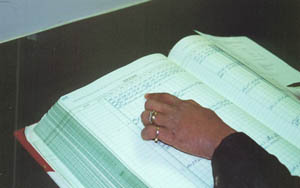

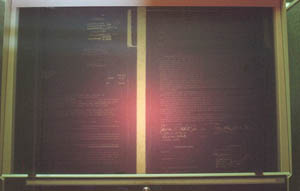

On January 11, 1997, the Documents of His Genesis came from the Children’s Services Society of Wisconsin, the agency that handled his adoption. The Documents provided his medical and social history, but any information that would identify or could be used to trace his people was blacked out, stricken from the record with what must have been a thick, black magic marker.

On January 11, 1997, the Documents of His Genesis came from the Children’s Services Society of Wisconsin, the agency that handled his adoption. The Documents provided his medical and social history, but any information that would identify or could be used to trace his people was blacked out, stricken from the record with what must have been a thick, black magic marker.

The next day, Craig met again Jacobus called Job on the Internet while he was looking for colleges in Huntsville, Alabama (the striker of record slipped up and left that location uncovered), the place where the Documents said she had attended college.

Eight years had passed since he first met Job and he knew then, as he knew now, that this was the man with whom he would spend the rest of his life.

A photograph, which he had found that very morning, of Seldon called Roy sat atop the computer looking down on him, bearing witness to this Internet reunion.

Seldon called Roy was his savior. A savior rarer than the name Seldon was given but never called. Craig had misplaced the photograph five years prior and had not seen it since. But almost out of nowhere, it appeared. When Craig moved his desk in order to retrieve his favorite pen, which had fallen behind it, Roy’s photograph was right there, face up, lodged between the heating pipe cover and the white brick wall.

And so the photograph of his savior also bore witness to him finding Oakwood College on the Internet. Oakwood College. The only religious-affiliated college in Huntsville, Alabama. Affiliated not with the Latter Day Saints, as the Documents of His Genesis erroneously indicated, but with the Seventh Day Adventists, who base their religion on the Three Angels Message from Revelation 14:6-13. Besides, Craig knew no black Mormons, several black Adventists, and the Documents of His Genesis identified his people as Negro.

And so the photograph of his savior also bore witness to him finding Oakwood College on the Internet. Oakwood College. The only religious-affiliated college in Huntsville, Alabama. Affiliated not with the Latter Day Saints, as the Documents of His Genesis erroneously indicated, but with the Seventh Day Adventists, who base their religion on the Three Angels Message from Revelation 14:6-13. Besides, Craig knew no black Mormons, several black Adventists, and the Documents of His Genesis identified his people as Negro.

Oakwood College. This must be where I was conceived, thought Craig. And so, along with Gail the Writer and Darlin the Musician, he poured through the Documents of His Genesis looking for any sign that might tell them who she was and where he could find her.

The social history was typed. Craig realized that they could count how many letters and spaces were behind the black streaks simply by comparing their length to the lines above or below. Sometimes the marks left tiny bits of letters discernable to their six eyes.

The social history was typed. Craig realized that they could count how many letters and spaces were behind the black streaks simply by comparing their length to the lines above or below. Sometimes the marks left tiny bits of letters discernable to their six eyes.

When they finally calculated that her first name was eight letters, beginning with the letter j, an i, or a t and ending with an r, and that her last name was five letters ending with an e, the first thing they thought was Jennifer White. The second thing they thought was Jennifer was right, but White was not. That would have been too easy. Much too easy.

And so they dismissed White as quickly as they thought it up in the beginning and Craig retreated to a place with no light.

6

On February 13, 1997, secrets and lies was nominated for an Academy Award™ for Best Picture, as were the actresses who played the seeker and the sought in their respective categories. Job asked Craig if they could see the film together, and he replied, “I don’t know if I will ever be able to see that movie again.” Certainly if I never find her, he completed the thought to himself.

On October 28, 1997, Job took Craig to see Lloyd Sheldon the Revelator at Black Star Enterprises in Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To Lloyd Sheldon, Craig revealed his date of birth. He revealed nothing else.

Among other things, the Revelator, who kept his eyes closed, revealed to Craig, speaking while writing:

Your psychic number is 8; your life number is 7.

You have lived 100 years in 30!!

You are most complex! Very few people understand you.

There is distance from your father; your natural father is far away from you. He has strong features and you look just like him. There is some connection to the family in Maryland / Washington D.C. / North Carolina / Virginia / Georgia. You’ll go to France, Holland, Belgium?? Germany in nearly 2 weeks, 10 days to 2 weeks. Be sure to take a camera on your trip. You have been searching long and hard for information. This has taken a lot of time. It is very important, tracing family. One ancestor is bi-cultural—*African American and Caribbean. You are not looking in the right places. If you really want to know—look. Your name was different. Birth certificates were changed. There is a Great Book inside of you that you have yet to write. It comes after you find what you are looking for. You have manuscripts that will be considered. If you are wise, you will collapse two into one!

*You will be reunited with your origins inside of four years. You must do the research!! Yourself. In person.

Lloyd Sheldon spoke and wrote many other things on the three pieces of wide-ruled paper he folded like a letter and put in a gray number 10 envelope. On the face of it, he wrote the date and handed it to Craig. On their way home, Craig read its contents to Job. He wouldn’t read it again until October 25, 2001. While compiling primary material for the big project he was about to undertake, Craig found the envelope stuck like a bookmark in the black journal he thought he’d lost years before.

7

On Craig’s thirty-third birthday, December 8, 2000, Job made more than a mess of things.

And so Craig told Job that this would be the very last birthday he would ever allow a mess to be made of, his birthdays being already so empty.

In the first three months of the following year, Craig lost himself in his work; he became short-tempered and ornery; he separated emotionally from Job. For more than forty nights, he could not sleep.

His boss, Octavio, had a baby boy, his firstborn son, and everyone in his office was able to hold the newborn, except Craig.

And he saw himself in this firstborn, held by the newborn’s mother, and his chest was heavy with pain.

And so she appeared in his daydreams, for he could not sleep at night, her face shrouded with hair.

He could not see her face, which was shrouded with hair, and his chest was heavy with pain.

And somewhere in the midst of this, Job took three weeks off from work, completed and defended his dissertation at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. Thus, after an eight-year journey to receive his Doctor of Philosophy, he would graduate the Sunday following Mother’s Day.

And somewhere in the midst of all of this, the 1967 Yearbook came from Oakwood College Archives.

And the yearbook revealed that he and Darlin and Gail had been right in the beginning: she was, indeed, a White girl. Jennifer White. So he was a White, too. Joseph B. White. And his uncle was a White, III. James E. White III. All J’s. His and hers.

And there, near the back of the book, in the college directory, it was—the permanent address where Jennifer lived when he was conceived: 3232 North Sixteenth Street on Milwaukee’s north side, just around the corner from the first home he lived as a Hickman on Thirteenth Street.

He used the address listed to search for James White, III on the Internet. It took a month, but all he could find was the telephone number of an England Martanna White, who lived on Ella Lane in Dalton, Georgia, and had been married to a James E. White.

This James E. White, born October 25, 1924, had died August 24, 1998, and had apparently lived within the past ten years at the same address on Sixteenth Street.

Was England of Ella Lane in Dalton, Georgia his grandmother? The woman who had orchestrated, according to the Documents of His Genesis, the entire drama unfolding therein?

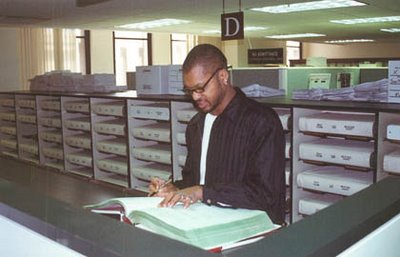

The real estate archives in the Milwaukee County’s Register of Deeds could tell him.

8

On April 1, 2001, Craig shared the Documents with his beloved friend and next-door neighbor, Joseph the Leo. And Craig said, “I must find her. Will I ever find her? I just have to. I wanna know things that only she can tell me. Do you think she’s thought of me all these years?”

And Joseph replied, “You have sisters. And she has told your sisters about you.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I just do. You have sisters. You have three sisters and she told them about you. And yes, Joseph, you’ll find her.”

Craig could hardly contain the earthquake. So he ran home to Job, who he had been separated from emotionally for three months, and he fell on their bed, and more water came.

And Job, saying nothing, held him, and Craig broke wide open and cried a river. When it dried up, Job asked, “What is it that you need from me? What can I do?”

“You need to take another week off from work. We need to go to Milwaukee. And we need to drive.”

And so it was that, without hesitation, Jacobus called Job, a man of hesitation, simply replied, “Okay.”

They knew the time was near.

(To be continued...)

From Fumbling Toward Divinty, copyright 2005. All rights reserved.