Inside, Job and Craig navigate its wide, sky-lit hallways and expansive rooms until they locate the rows and rows of flat drawers full of boxes and boxes of the nation’s archived newspapers. Craig searches through volumes of the Milwaukee Journal and the Milwaukee Sentinel, looking for the obituary of James E. White where he hopes the full names of his children will be listed. Job searches through editions from 1970 to 1985 hoping to find a Jennifer White in the marriage announcements. After two hours of loading up, scrolling through, and unloading countless cartridges of film, they find nothing, pack their notes, and move on to the courthouse.

The Milwaukee County Courthouse stands just behind the Milwaukee Public Library on Ninth Street. Its architecture nearly eclipses the restrained beauty of the library in grandiosity and scale. Like the library, the court-house’s architectural design resulted from a nationwide competition. Faced with Bedford limestone, the courthouse features columns on all sides, stone owls, lioness’ heads, and inscriptions, all of which reminded Craig of the renditions of the pre-ruin Parthenon he’d seen in books from his high-school Latin class. The courthouse was completed in 1932 for eight-and-a-half-million dollars and in 1976, it was designated a National Landmark.

“I wanna know where I can find historical property records for this address,” Craig says to the woman with the dark-brown bob behind the help desk.

“Is the property in Milwaukee County?”

“Yes.”

“Then the first thing you’re gonna need to do is go back upstairs to the treasurer’s office and get the legal description of the property. Once you have that, come back to me and I will show you where you can find what you’re looking for.”

“Thank you,” says Craig, turning away. He turns back to the woman. “By the way, what is your name?”

“Ann. I’m the only one here today.”

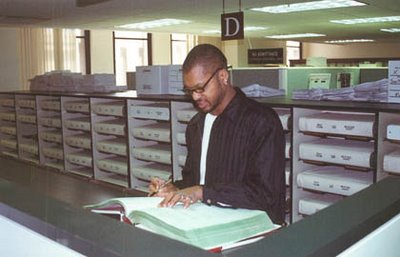

Job walks around through the stacks of case-bound books while Craig goes to the county treasurer’s office to get the legal description. When he returns, Craig rings the help-desk bell. Ann comes over and tells him how to proceed. “How far back are you looking?”

“I need to get information from the sixties, maybe the fifties.”

“All records before ninety-six are on microfiche. Follow me.” She leads Craig over to a row of computers. “Here you’ll follow the instructions on the screen. Type in the legal property description. You will get a number. That number includes the book number and page number of the documents you want.” She leads Craig into the stacks where Job still looks around. “Over here, find the number of the book. Go to the page with your property description. You’ll see a column with volume numbers and a column with film numbers. Each time the property changed hands, or there was some event at the property, a foreclosure perhaps, there’s an entry in the register. Select the ones you want and then come over here,” she leads Craig back to the help desk, “fill out these cards and give them to me. I’ll bring you the microfiche, which you take over to the viewers just opposite the computers. Do you know how to use the viewers?” “I’m sure I can figure it out.”

“I’m sure I can figure it out.”

“Well, let me know if I can be of any help. Good luck.”

Job has come out of the stacks. “Did you hear any of that, honey?”

“Some of it. What do you need me to do?”

“Nothing, I don’t think. I guess I’ll just go ahead and get started.”

Within half an hour, Craig is sorting through microfiche on one of the viewers. Ann has given him the deeds from 1950 to 1992. During that time the property changed hands only three times.

The third time was the charm.

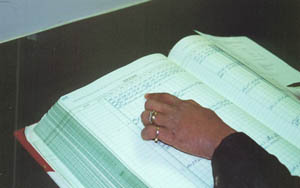

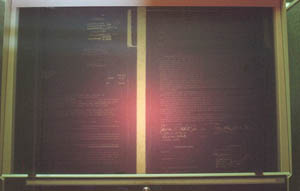

For there, on the third transaction, are the instructions, the text a constellation set against the midnight-blue sky of film, able to be seen as the light filters into its spaces from the bulb behind the screen. The stars say that after the sale of the house in 1992, Iretha Starr-Johnson, the new owner, whose tiny signature is almost indiscernible, was to send all loan payments to the address at Ella Lane in Dalton, Georgia. James E. White, Jr. and England White, the sellers, also signed the deed.

“Job, come here.” Job rushes right over when he sees Craig’s face, transfixed by the heavens. “Look.”

“Wow. There they are.”

There they are, or what Craig can see of them, smell of them, feel of them through their signatures. James’ signature is entirely legible, executed with perfect penmanship, the neatest signature of any man, except perhaps his own father’s, that Craig has ever seen. It is the signature of an artist. England’s signature, also entirely legible, nonetheless, seems marred by restraint, as though her hand could not flow freely through the strokes as it created them. It is the signature of a person under perpetual duress. For what seems to Craig like hours, he stares at these signatures—dissecting, re-arranging, tracing them—as though they are the DNA on which his own genetic code is signed.

“I’m gonna take a picture.” And so Job does.

Now they know it without any doubt. Craig rifles through his briefcase, finds the Internet printout for the deceased James E. White and studies it; the woman in Dalton Georgia is, indeed, his grandmother. He holds her telephone number in his hands.

Sitting in the bowels of a building that will, without a doubt, someday be considered a classic, Craig holds another whole world in his hands.

TAGS: Milwaukee, Milwaukee County Courthouse, Milwaukee Public Library

No comments:

Post a Comment