Musings about art, life, spirit and love by an adult adoptee living in reunion.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

A Year Ago Today....

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Thursday, December 08, 2011

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Friday, November 11, 2011

Saluting Our Veterans

Sunday, November 06, 2011

Friday, October 21, 2011

Food Is Life: Remarks to Students at Maranacook Community School, October 20, 2011

A wise man once said, “There’s a hunger beyond food that’s expressed in food, and that’s why feeding is always a kind of miracle.”

There’s a hunger beyond food that’s expressed in food, and that’s why feeding is always a kind of miracle.

::

Back when I was a kid in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, our family struggled to make ends meet. My father worked the first shift at Pabst Blue Ribbon Company in the mail room. A World War II veteran with little education, he was basically the company mailman. My mother held a string of part-time jobs to help put food on the table for their two children. As hard as they both worked, and they worked hard, we needed food stamps in order to survive. Still, my parents made clear in both word and deed that no matter how little we had, someone else had less and we needed to help them however we could.

I’ll never forget the day. I was about three or four years old when a young girl who smelled of dried urine knocked on our door. My father was at work, my sister at school. My mother let the girl in and escorted her to the bathroom where she drew a bath for the girl, who couldn’t have been more than 12 years old. After bathing her, my mother gave her a blouse and a pair of pants and sat her down at the kitchen table for a steaming bowl of Cream of Wheat, bacon and toast. I couldn’t believe how fast the girl devoured it all. It was an image that stuck with me, like good preaching. She ate another bowl of cereal and then my mother let her take a nap on the couch. Later, when it was time for her to leave, my mother handed the girl a brown paper bag with a change of clothes and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich inside.

I couldn’t count how many girls came knocking on our door over the next months, but they came nonetheless. My mother cared for each of them in almost the exact same way, like ritual. Our home was a stop on an underground railroad for throwaway girls.

It’s no surprise, then, that I would turn my current home into place where anyone, no matter their need, can come at any time, no questions asked, and receive food.

If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes an entire community to feed an entire community.

::

Food is life.

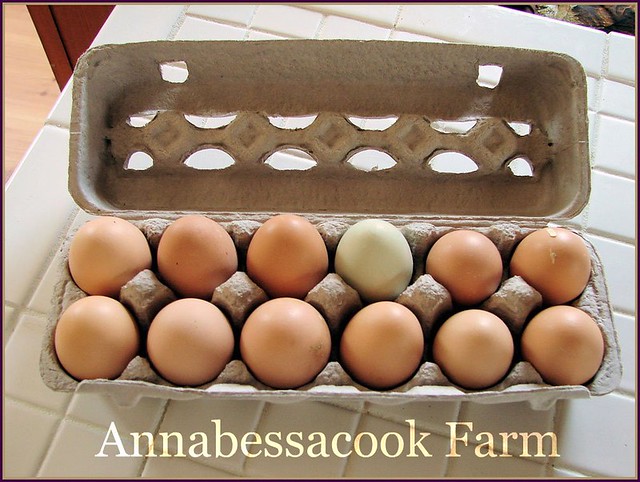

When I first made the community aware a year ago that free food was available at the farm 24-7, I heard all sorts of caveats and concerns. “What if someone takes all the fresh food from your farm stand and goes out and sells it?” Where is the love in that question? “Then I guess they need the money to make their rent or pay their mortgage,” I replied. “How can you be so sure that the people who take it really need it if you don’t ask any questions?” You can’t.

But so what.

Last Wednesday, during preparations for the Hot Meal To-Go at Annabessacook Farm that the Winthrop Hot Meal Kitchen provides each Wednesday until we can find a permanent home to provide food and fellowship for people each weekday, a woman called to ask if we still had half a bushel of tomatoes to sell. Her voice sounded vaguely familiar, but I didn’t recognize whose it was. I told her we did and asked her what she wanted them for. “Canning,” she said. “Then we have some left to sell,” I replied. It’s late in the year and tomatoes have pretty much gone by, but we were lucky enough in recent weeks to harvest another three bushels perfect for canning because most of our plants grew in a greenhouse film-covered tunnel in the middle of the field behind the barn.

“How much are you asking for them?” she asked timidly. From her tone, I sensed she had need.

“How much are you offering?”

“10 bucks,” she replied, a question mark still in her voice.

“Perfect. Do you know where we are?”

“Oh, yes. I’ll be over this afternoon.”

Hours later, a woman walked up to the door, a woman I hadn’t seen since last summer. From September through November, she came once or twice a week and purchased pounds of Swiss chard, bushels of tomatoes, cartons of squash. She was preparing for winter and I was honored she chose our farm to buy the food she would process for her family.

“I haven’t seen you in a long time.”

“I’m unemployed now.” The look on her face broke my heart.

“Was it you who called earlier about tomatoes?”

She nodded. I nearly lost it. I wouldn’t call her my friend – we don’t hang out and do stuff together or anything – but she’s certainly my neighbor. I knew she worked for the State of Maine and with all the recent budget cuts, it didn’t surprise me that she’d lost her job. I also knew she had a big extended family to feed and here she was on my doorstep knowing we give away food but offering to buy a half bushel of tomatoes nonetheless.

I tried not to be awkward. I’m not sure I succeeded.

“Um. Well. It’s Wednesday and we offer a free hot meal today in addition to the fresh veggies. Would you like one?”

She shook her head, eyes cast down at the ground upon which we stood.

“We’ll, I’ll be insulted if you don’t take some of this food I cooked, so here.” She obliged. I gave her four meals, asked her to put them in her car and meet me in the garage so I could show her where the tomatoes were.

She handed me the 10 bucks before walking to her car. I didn’t refuse the money because I’ve been poor and hungry and it still never felt right to me to take anything for free since I was lucky enough to always have a few dollars to give. Clearly, she felt the same way. I didn’t want to insult her either.

After we showed her which box to fill up with organic tomatoes, my godson and I left her alone in the garage where all of our fall harvest is stored. Winter squash and pumpkins. Melons, carrots, turnips, rutabagas, and beets. Potatoes, sweet potatoes, cabbage, onions and leeks.

We sat in the kitchen and watched her through the window put the box of tomatoes in her car. Then she went back and got two more boxes of something else. That made my heart sing.

And so it was that a woman in need called on a hot-meal Wednesday offering to buy tomatoes so she wouldn’t feel shame about coming to receive the food she needed. That’s called pride. And I know there are lots of people like her who would never use a traditional food pantry they’d have to sign-in for because their pride simply wouldn’t allow it.

When she was leaving, she saw my godson and expressed her gratitude with a smile. “Tell Craig thanks so much for everything.”

If you saw her walking down the street, you probably wouldn’t think she was hungry. That she needed food. You can’t always tell. You just can’t. You can’t ever be sure the level of need a person has, but know this: everyone has a right to food so we must make sure we don’t keep anyone from the table. No one among us should go hungry for a single day. Put another way: we cannot allow a single person among us to go hungry for a single day.

::

Now make no mistake, feeding people isn’t a selfless act. We’re only as strong as the least among us, so if one person is hungry, we’re all hungry. Moreover, the miracle of feeding people that the wise man I mentioned earlier spoke of happens as much inside the person giving the food as it does in the person receiving it. That’s how love works. The act of giving brings me joy. Pure joy.

Sometimes I happen to be in the music room in the front of the house when I see someone through the window gathering food off the farm stand by the side of the road. Much of the food there disappears in the middle of the night so if I catch a chance during the day, I always stay and watch until they’re finished. What will they take? What do they like to eat? What do I need to grow more of next year? I’ll watch them fill up a bag and drive away. Sometimes a person will sample something – a string bean or a cherry tomato – and decide it’s not sweet enough or firm enough and they’ll choose something else. Sometimes I feel like I’m spying on them, but hey, they can’t see me inside, it’s all out in the open anyway, so I get over myself and allow my writer’s curiosity to win out. When I watch a hungry person or a person in need have a chance to actually choose what they take to eat, I smile then. Or laugh out loud, rain falling from my eyes.

::

Food is life. People who want to live need to eat. And there’s no reason whatsoever why we can’t come together as a community and feed them. I’m going to say that again:

People who want to live need to eat. And there’s no reason whatsoever why we can’t come together as a community and feed them.

So go, young people. Go. Out into the community and collect as many pounds of food as you can collect for the agencies in your community that feed the people.

Food is life.

Now go. Make miracles.

Saturday, October 15, 2011

A Humbling Thing

::

Hot Meals Kitchen feeding hungry from B&B, not church

Group finds way to keep making meals for those in need

By Betty Adams badams@centralmaine.com

Staff Writer

STIRRING THE POT: Craig Hickman, owner of Annabessacook Farm Bed & Breakfast, cooks a hot meal on Wednesdays for the benefit of dozens who formerly accessed a free lunch at St. Francis Xavier Church Hall. He ran in the most recent race to represent District 82 in the Legislature and served as secretary of the Hot Meals Kitchen board. Staff photo by Andy Molloy

::

WINTHROP -- Open the kitchen door and take in the aroma. Barbecuing chicken, baking ham and roasting pork fill ovens and a grill.

Mushroom and herb stuffing and butternut squash bake in the oven. Mashed potatoes, leeks and curried collards simmer on the stove.

It's Wednesday, and the hot gourmet food is destined to feed hungry people in Winthrop and surrounding communities.

The savory symphony is the work of Craig Hickman, owner of Annabessacook Farm Bed & Breakfast, who cooks a hot meal on Wednesdays for the benefit of dozens who formerly accessed a free lunch at St. Francis Xavier Church Hall.

The arrangement was supposed to be temporary.

Then, this week, St. Michael Parish administrator the Rev. Francis Morin announced the Hot Meals Kitchen will no longer operate in St. Francis Xavier Hall.

Morin said earlier an inspection of the Hot Meals Kitchen program by the Diocesan Property Management Office, which manages the St. Francis Xavier church property, found the program lacked a board of directors, an up-to-date tax ID number and liability insurance.

In a cost-cutting move, the parish also sought rent from the kitchen.

"It was not an easy decision, but we asked the soup kitchen board to pay rent to the parish of $400 a month," Morin said.

On Monday, he withdrew that offer in a letter to Hot Meals Kitchen board chairman Robert Pelletier.

"It has been over a month since the original deadline ... to get all in order for the parish to consider permitting the reopening of the Kitchen at the parish site," Morin wrote. "Since this has not occurred and we are into the month of October and the board has resisted the issue of the payment of rent to the parish, I have finally decided that it would be best for the board to find a more appropriate site to continue its service."

Read the rest....

Related Posts

For I Was Hungry And You Gave Me Food

Giving Thanks

Sunday, October 02, 2011

Giving Thanks

Thank you to the little boy who came to the farm one Sunday afternoon with his mother. He had raided his piggy bank of pennies, nickels, dimes and quarters, rolled them all up, carried them up the walkway and put them in my hands. Surely, a child shall lead them.

Thank you to the 50 people, mostly from our community, but from as far away as Wisconsin and New Mexico, who contributed $3,600 or pledged more if needed since September 3. We also give thanks to all the people who anonymously left cash at the door or have offered their help to cook and serve a meal.

Thank you to St. George’s Episcopal Church in New Orleans, Louisiana, for your generous contribution to a soup kitchen way up here in Winthrop, Maine.

Thank you to Phoenix Farm for donating bushels of tomatoes, boxes of cucumbers, and hundreds of pounds of potatoes so our hot meal every Wednesday can feature organic, local food. Thanks also to the singing woman who brought bags of fresh fallen peaches every week till her trees said no more, the man who did the same with his apples, the young man who brought a big bag of cucumbers from his garden, and the man who donated seeds to grow part of next spring’s meals.

Thank you to the young woman who walked up one Wednesday bearing whole grain biscuits. They were good as heaven. Her heart was open. So open. "I'm just here for the people,” she said. “Call on me whenever. I'll peel garlic. Anything at all. I don't care. I'm just here for the people." She brought banana muffins the next week.

Thank you to a neighbor who made minestrone, a woman who made potato salad, the young woman who made seafood chowder and apple pie, and the couple who baked brownies, chocolate chip cookies, and pineapple bread. All of it was marvelous.

Thank you to the man who drove all the way down from Waterville one Wednesday to drop off savory baked ziti with sausage to round out a nutritious meal just as the potato salad ran out.

Thank you to the couple who delivered a trailer load of sturdy shelving so we have a place to store dry goods, the woman who cleared out her freezer of Kentucky ham and her cabinet of canned goods, dried beans and pasta, and all the people who dropped off bags and containers and cartons.

Thank you to the members of American Legion Post 40, Camp Mechuwana, and the Winthrop United Methodist Church for trying to find a way to make a home for the soup kitchen at your facilities. We also thank the people who suggested other locations, such as the Winthrop Grange or the Masonic Lodge.

Thank you to all the concerned citizens in Kennebec County who attended our last board meeting to offer invaluable advice on how to move forward.

Last, but certainly not least, thank you to the parishioners of St. Francis Xavier who have wholeheartedly supported the soup kitchen for more than 25 years with your contributions and your time. To this day, you rally to keep the soup kitchen right where it’s been to continue the mission of feeding the hungry. As a wise bishop once said, “There’s a hunger beyond food that’s expressed in food, and that’s why feeding is always a kind of miracle.” And so we give thanks to the people of the church who’ve made so many small miracles for so many of our most vulnerable citizens over so many years

Amidst this outpouring of support from our awesome community, we’re still searching for a home. Until then, we’ll continue serving a hot meal to-go every Wednesday at Annabessacook Farm, 192 Annabessacook Road in Winthrop. Meals are available, no questions asked, on a first-come, first-serve basis from noon until 6pm. If you know someone in need but maybe too proud to take one or who simply can’t get around, then pick up a meal and take it to them. Please. If you have any questions, call 377-FARM. And if you’d like to contribute to the cause, please send a donation to Winthrop Hot Meal Kitchen, P.O. Box 472, Winthrop, ME 04364.

Wherever we go from here, you can follow our progress on our Facebook page where you can access meeting schedules, minutes and menus. Together, we can do this. Together, we will.

Thank you again. Take care of your blessings.

(This essay first appeared in the Community Advertiser on October 1, 2011. Cross-posted to Winthrop Hot Meal Kitchen.)

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Sunday, September 04, 2011

For I Was Hungry And You Gave Me Food

“There’s always hope,” I assured them.

The business manager of the diocese that oversees the parish is asking $400 per month in order for us to remain there. $400 is way too steep and the board of directors has not agreed to pay it. As far as I’m aware, the soup kitchen has never paid rent before and we simply cannot afford it now. Such an expense would put us in the untenable position that many struggling families face every day – do we choose to buy food or pay the rent?

“If you think there’s hope that it’ll re-open, then I have something for you.”

The gentleman reached into the left chest pocket of his blue shirt and pulled out two folded $50 bills.

“This is from an anonymous donor. You may have it for the soup kitchen if you promise me none of it goes to the church.”

::

Back when I was a kid in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, our family struggled to make ends meet. My father worked the first shift at Pabst Blue Ribbon Company in the mail room. A World War II veteran with little education, he was basically the company mailman. My mother held a string of part-time jobs to help put food on the table for their two children. As hard as they both worked, and they worked hard, we needed food stamps in order to survive. Still, my parents made clear in both word and deed that no matter how little we had, someone else had less and we needed to help them however we could.

I’ll never forget the day. I was about three or four years old when a young girl who smelled of dried urine knocked on our door. My father was at work, my sister at school. My mother let the girl in and escorted her to the bathroom where she drew a bath for the girl, who couldn’t have been more than 12 years old. After bathing her, my mother gave her a blouse and a pair of pants and sat her down at the kitchen table for a steaming bowl of Cream of Wheat, bacon and toast. I couldn’t believe how fast the girl devoured it all. It was an image that stuck with me, like good preaching. She ate another bowl of cereal and then my mother let her take a nap on the couch. Later, when it was time for her to leave, my mother handed the girl a brown paper bag with a change of clothes and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich inside.

I couldn’t count how many girls came knocking on our door over the next months, but they came nonetheless. My mother cared for each of them in almost the exact same way, like ritual. Our home was a stop on an underground railroad for throwaway girls.

::

When you walk into the parish hall at St. Francis, a collage of old photographs hanging on the wall to the left catches your eye. Emblazoned on plaques amidst the images of days gone by are the words “Feed the Hungry” and “Clothe the Naked.” For more than 25 years, volunteers have served thousands in the hall who need the food and the fellowship they receive there to survive. Is there anything more nurturing and sustaining than sitting down around a table and breaking bread with people?

Now, the food and fellowship needed by many families in our community are threatened because church representatives say the church cannot afford or does not want to continue to host a soup kitchen on its premises without expensive “help” from the volunteer organization that fulfills an essential part of the church’s mission. The business manager made it as clear as silver striking crystal.

“Don’t you people have anywhere else you can go?”

She looked me directly in my face at our last board meeting and asked that question. A question that seemed to betray the good faith negotiations I thought we were having about the $400 per month in rent the church is asking for us to remain and serve the community. You see, the money was needed to help pay for the electricity the old freezers and refrigerators in the basement of the church consume. Or so she had told us this past spring. Make no mistake, no appliances, no matter how inefficient, consume $400 in electricity each month. Still, we wanted to work something out. So when we offered to replace the old ones with brand new energy efficient appliances, something we ought to do anyway, and reduce the electrical costs to a mere $30 per month, she refused to budge from the $400.

“It’s not just the electricity, but it’s also the heat and the snow removal, and…”

“We don’t use any heat,” I said.

The stoves emit enough heat to warm the entire parish hall when they’re fired up for the soup kitchen. Since another group pays for the propane that fires the stoves, the soup kitchen doesn’t incur any costs for the fuel that not only cooks the meals but heats the space in the cold of winter.

“If snow removal is now also on the table,” I offered, “then why don’t we operate the kitchen during the months when there’s no snow and close it in the snowiest part of winter?”

“You can pick apart this $400 all you want,” she continued, “but you should know that we just recently had to pay out an $11,000 claim for a woman who fell on the lot. Do you even know about this fall?”

“Well, yes,” replied the chair of our board, who also happens to be a member of the parish. “I was walking with her. I was the one who helped her up and called for help.”

Silence fell over the room like prayer. Many of the board members dropped their heads and averted their eyes as though they were ashamed of the exchange they just witnessed. How could it be that this business manager would assume an active member of the church wouldn’t know what happened on the property? Especially when this same member can cite chapter and verse the amount of money the church collects in offerings every Sunday. This money, this bread, if you will, cannot go to defray the cost of the soup kitchen because it travels like a prodigal son to Augusta every week. To be spent on whatever the higher-ups there decide. This according to the testimony of every representative of the parish who has attended our summer board meetings.

In short, the Winthrop Hot Meal Kitchen was not able to re-open in time for the start of school because the business manager responsible for the church’s bottom line sees every person who uses the kitchen as a big old dollar-sign liability. Consequently, if we are to remain where we are and serve the people who want the soup kitchen to remain right where it is, we have to cough up $400 per month to help defray the cost of the church’s liability claims. Not the electric bill, or the heating bill, or the snow removal bill, but the liability claims. How am I so sure? Because the business manager of the diocese looked me in my face and mentioned its liability claims four times in seven minutes. She even referenced a copy of the recent claim she didn’t think any of us knew about which sat on the table right in front of her. Oh, yeah. She also wants us to purchase our own liability insurance policy.

How did we get to this place? It’s no longer in the church’s budget to feed the hungry and clothe the naked? Isn’t “love thy neighbor as thyself” a principal tenet of Christianity?

My mother, who still lives in the same house in Milwaukee where I grew up, is 83-years-old, widowed, and battling cancer. Mostly through her church, she still helps those less fortunate than she, feeding the hungry, counseling teenage unwed mothers, providing hand-sewn quilts to those who will be cold this winter. She simply cannot fathom this story I told her about our soup kitchen the other day. Could. Not. Fathom it. I can’t actually write what she said but she had to put her religion down in order to say it.

It seems that everywhere I turn these days some super-sized corporate entity, for-profit or not, stands between us and our ability to care for our most vulnerable citizens.

I would imagine this is why the man representing that anonymous donor walked up to my door on August 22 and asked me to promise him that no part of those two folded $50 bills he put in my right hand would go to the church.

::

“Isn’t there somewhere else you people can go?”

You better believe it. We the people will make a way out of no way, if we must, and find a place to serve a nutritious hot meal to those who come up my driveway or stop me at the grocery store to ask me when and where the soup kitchen will re-open.

I said it before and I mean it again: People who want to live need to eat. And there’s no reason whatsoever why we can’t come together as a community and feed them.

So, if you’re with me, then join me. Please. Give us this day our daily bread. Send a check made out to the Winthrop Hot Meal Kitchen, no amount too big or small, and mail it to P.O. Box 472, Winthrop, ME 04364. You may also click on the "Donate" button below. If you have a facility in Winthrop or the contiguous townships with a commercial kitchen and hall that can seat and serve 50 people every weekday, as well as a space on the premises for two large freezers, a refrigerator and ample dry-good storage, please step forward. If push comes to shove, we’ll open the earth and build a facility from the ground up. We must ensure that those who depend on our soup kitchen for sustenance and fellowship will not be displaced or inconvenienced.

It’s the least we can do for the least among us.

In the meantime, I’ll prepare a simple hot meal every Wednesday and put it in to-go containers for pick up at Annabessacook Farm at 192 Annabessacook Road in Winthrop. It may only be beans and rice or macaroni and cheese, but it will be something. The meal will be available on a first-come, first-serve basis starting at noon every Wednesday, come rain, snow, sleet, or shine. If there are leftovers, I’ll freeze them and make them available throughout the week at our food bank. Call 377-FARM if you have any questions or would like to help. Take care of your blessings.

(This essay first appeared in the Community Advertiser on September 3, 2011)

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Monday, August 22, 2011

Friday, July 22, 2011

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Till Death Do Us Part

Her man's gone now. Ain't no use a listenin' for his tired footsteps climbing up the stairs.

But I'm sure she can still feel his presence on the day that will always be one of the best days of her life. Always be her wedding anniversary.

And he'll always be her one and only love.

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Sunday With Luther :: Dance With My Father

WISHING all the fathers out there a peaceful and blessed Father's Day.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Sowing, Praying

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Monday, May 02, 2011

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Happy Fertility And Rebirth

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Spring Babies At Annabessacook Farm

A slideshow of baby goats Stew and Boter, and our surprise lamb Mushroom, born in the rain and mud. Best viewed in full screen mode.

Thursday, March 31, 2011

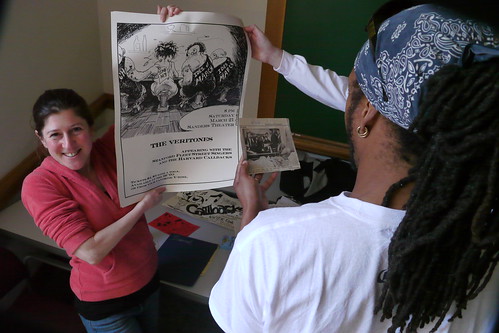

Silver Striking Crystal: The Harvard Callbacks Sterling Anniversary Jam

On September 1, 1986, according to official records, I founded the Harvard Callbacks along with Morgan London, then called Dawn Clark, two legal name changes earlier. Both voluntary, one by marriage. I, too, have had a legal name change. Involuntary. By adoption. That the two of us would join to found what can be described as a family and an a capella singing group is beyond serendipity.

I'm looking at some piece of memorabilia here. Probably the photo of us singing for the elderly at Neville Manor as seen below.

You see, the Callbacks saved my life. Saved Dawn called Morgan's life, too. I was probably the most depressed I've ever been in life during my college years. I get the feeling Dawn called Morgan was, too. And so our starting and participating in a group that defined our college years, that became a family we created for ourselves, literally saved our lives. And sustained them. Morgan Inniss, in changing her name from Dawn Clark, divorced herself from her biological family. Days after my birth, my biological family had divorced itself from me, then called Joseph White, till I found a home with a family as Craig Hickman.

The Paleo-Callbacks getting ready for our alumni set.

Debbie Steinbaum brought all the archival gems to pass along to the new generation. Here she holds a poster of the Veritones jam where we were invited as an opening act.

And so it was also beyond serendipity that Morgan and I would both fly to the Harvard Callbacks 25th Anniversary Jam from Florida; she from her home outside Jacksonville, me from a tennis event I was covering in Miami, where just the day before, I saw my birth father again for the first time since my 34th birthday in 2001. That her husband, whom I met for the first time at the jam but who seemed as familiar to me as the sun, would break down and cry during a performance of Sarah McLachlan's "Angel" remembering his father who'd died on Christmas day. That I had just visited my ailing mother in Milwaukee to observe the 4th anniversary of my father's death on March 14 before flying to Miami. And so it was no wonder at all that Dawn called Morgan and I would connect so profoundly back then, starting a family we never planned.

We just wanted to sing.

In Florida with my birth father, Frank. Photo by other half.

Our first president, Don Ridings, and his son Erik. This was the first reunion concert Don attended and I, for one, was ecstatic to see him.

When the dean of students wanted us to disappear, we persevered instead. We staged concerts in Paine Hall, Dunster House, and Leverett Dining Hall, among other places. No founding Callback ever hosted a jam in Sanders Theater. There were moments, at previous reunions, when I wish I knew the tenor parts of the songs the current group was singing. I would have jumped onto the stage and performed in the whole set just to say I finally got to do a whole show in Sanders. Instead, I remembered Paine Hall and hand-designed posters and tie-died banners. We had no budget. We had no vision.

We just wanted to sing.

We looked good and sounded even better.

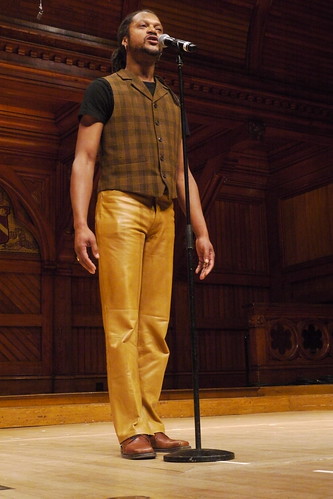

Doing the poetry slam thing. Read the poem right here.

25 years later, what we created has grown and changed and changed and grown.

The current group of Callbacks, many of whom weren't even thought about when Dawn called Morgan and I stood before Holden Chapel in Harvard Yard and declared that we would start a group (we wanted to sing, damnit, and nothing whatsoever was going to stop us), signed a card for each of us and presented them to us after the Sterling Anniversary Jam this past Saturday night.

"Thanks for helping define my Harvard experience," wrote one Callback.

"I'm so happy you founded the Callbacks -- it has become one of the most important experiences of my life. I'm so glad I got to meet you," wrote another.

And then there are these:

"Thank you so much for creating this family of singers. The CBs have been so essential and important in my life. Thank you!"

"The Callbacks have been a wonderful experience and a great addition to the Harvard community. Thank you so much for everything."

"Thank you for all your efforts in starting the CB's. The group has become my family."

"The Callbacks have filled the last 4 years with amazing music and wonderful memories. Thank you for starting the group that has become my family."

The more things change, the more they remain the same.

I did well to get through the concert without blubbering. Not so hours later when reading the card just before bed.

After singing our signature songs "Old Irish Blessing" and "The Letter", Chris Heller, the current president, gave Morgan and me each a beautiful bouquet of flowers. After, when we embraced, in front of family, before fans and friends, Morgan confessed in my ear, "This is the proudest moment of my life."

With six generations of Callbacks standing in a giant horseshoe on stage behind us, who had just demonstrated how much college a capella singing has evolved over the last quarter century, who now applauded enthusiastically along with the audience while we embraced, it was hard to think of another moment in life when I was prouder.

There's nothing more important than family.

(All Callbacks photos by Callbacks progeny, Lila Cardillo and Erik Ridings.)

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Sunday, March 06, 2011

Sunday With Ethel :: His Eye Is On The Sparrow

Sunday, February 27, 2011

Sunday With Sam :: A Change Is Gonna Come

Origins

Upon hearing Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind" in 1963, Cooke was greatly moved that such a poignant song about racism in America could come from someone who was not black[1]. While on tour in May 1963, and after speaking with sit-in demonstrators in Durham, North Carolina following a concert, Cooke returned to his tour bus and wrote the first draft of what would become "A Change Is Gonna Come". The song also reflected much of Cooke's own inner turmoil. Known for his polished image and light-hearted songs such as "You Send Me" and "Twistin' the Night Away", he had long felt the need to address the situation of discrimination and racism in America, especially the southern states. However, his image and fears of losing his largely white fan base prevented him from doing so.

The song, very much a departure for Cooke, reflected two major incidents in his life. The first was the death of Cooke's 18-month-old son, Vincent, who died of an accidental drowning in June of that year. The second major incident came on October 8, 1963, when Cooke and his band tried to register at a "whites only" motel in Shreveport, Louisiana and were summarily arrested for disturbing the peace. Both incidents are represented in the weary tone and lyrics of the piece, especially the final verse: There have been times that I thought I couldn't last for long/but now I think I'm able to carry on/It's been a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come.

Recording

After remaining confined to Cooke's notebooks for months of touring, "A Change Is Gonna Come" was finally recorded on December 21, 1963. Recording took place at the RCA Studios in Los Angeles, California during sessions for Cooke's 1964 album, Ain't That Good News.

According to author Peter Guralnick's biography of Cooke, "Dream Boogie", Cooke gave arranger Rene Hall free rein on the song's musical arrangement. Hall came up with a dramatic orchestral backing highlighted by a mournful French horn. For his vocal, Cooke reached back to his gospel roots to sing the song with an intensity and passion never heard before on his pop recordings.

Release

The song made its first appearance on Ain't That Good News, the last album to be released within Cooke's lifetime. The LP did well, peaking at number 34 on the Billboard Pop Albums chart, making it more successful than Cooke's previous LP, 1963's Night Beat.

However, Cooke and his new manager Allen Klein thought the song deserved greater exposure. According to Guralnick's book, Klein persuaded Cooke to sing "A Change Is Gonna Come" on his February 7, 1964 appearance on The Tonight Show. Cooke sang the song; unfortunately, any impact it made was dimmed by The Beatles' history-making appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show just two days later. In a further misfortune, NBC did not save the tape of Cooke's performance, which has never turned up in private collections either. RCA Records had bypassed "Change" for Cooke's early 1964 single, instead releasing the tracks "Good Times" and "(Ain't That) Good News". But the company agreed to put the song out as a single late in the year, as the B-side to Cooke's latest potential hit, "Shake." At one of his last recording sessions, Cooke approved an edit to the song that would shorten it by about 30 seconds, increasing its chance for airplay on American radio stations.

Finally given proper attention, "A Change Is Gonna Come" became a sensation among the black community, and was used as an anthem for the ongoing civil rights protests. On R&B radio, the song peaked at number 9 on the Billboard Black Singles chart, and topped many local playlists, most notably in Chicago. The song had more limited success on top 40 radio. By February 1965, the song had peaked at number 31 on the Billboard Pop Singles chart and fallen off. Cooke, however, did not live to see the song's commercial success. On December 11, 1964, he was killed at the Hacienda Motel in Los Angeles, California under what some consider mysterious circumstances.

Legacy

Though only a moderate success sales-wise, "A Change Is Gonna Come" became an anthem for the American Civil Rights Movement, and is widely considered Cooke's best composition. Over the years, the song has garnered significant praise and, in 2005, was voted number 12 by representatives of the music industry and press in Rolling Stone magazine's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, and voted number 3 in the webzine Pitchfork Media's The 200 Greatest Songs of the 60s. The song is also among three hundred songs deemed the most important ever recorded by National Public Radio (NPR) and was recently selected by the Library of Congress as one of twenty-five selected recordings to the National Recording Registry as of March 2007. The song is currently ranked as the 95th greatest song of all time, as well as the seventh best song of 1965, by Acclaimed Music.[2]

Despite its acclaim, legal troubles have haunted the single since its release. A dispute between Cooke's music publisher, ABKCO, and record company, RCA Records, made the recording unavailable for much of the four decades since its release. Though the song was featured prominently in the 1992 film Malcolm X, it could not be included in the film's soundtrack. By 2003, however, the disputes had been settled in time for the song to be included on the remastered version of Ain't That Good News, as well as the Cooke anthology Portrait of a Legend.

"A Change Is Gonna Come" was a precursor to many later socially-conscious singles, including Marvin Gaye's lauded "What's Going On". Al Green, a self-professed fan of Cooke, covered the song for the concert celebrating the 1996 opening of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Green's live rendition was included in the soundtrack to the 2001 Michael Mann film Ali. James Taylor recorded a version specially for an episode of the same title of the television drama The West Wing. The Allman Brothers Band captured their performance of the song on their 2003 DVD Live at the Beacon Theatre.

Other notable artists who have covered the song include Allison Moorer, Jeffrey Gaines, Matt Doyle, Cory Wells, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, The 5th Dimension (in a 1970 medley with The Rascals' "People Got to Be Free"), The Band, Wayne Brady, Billy Bragg, Evelyn Champagne King, Solomon Burke, Terence Trent D'Arby, Gavin DeGraw, the Fugees, the Cold War Kids, The Gits, Deitrick Haddon, Patti Labelle, Solo, Prince Buster, Morten Harket, The Neville Brothers, jacksoul, Ben Sollee, Johnny P, Billy Preston, Otis Redding, Baby Huey (singer), Michael Thompson featuring Bobby Womack, Leela James, Tina Turner, The Righteous Brothers (Bobby Hatfield solo), The Gits, Brandy, and The Supremes, The Manhattans, Gerald Alston, Arcade Fire has used the song in support of Barack Obama's nomination for President of the United States. In recent years, the song has served as a sample for rappers Ghostface Killah (1996), Ja Rule (2003), Papoose (2006), Lil Wayne (2007) "Long Time Coming (remix)" Charles Hamilton, Asher Roth, and B.o.B (2009), and Nas's It Was Written album also features a similar opening as the song. On their album The Reunion hip-hop artists Capone-N-Noreaga used an excerpt from the song on the opening track which shares the same title as the Cooke original. British soul singer Beverley Knight says the song is her all time favourite and has performed it live many a time; most notably on 'Later with Jools Holland'. On May 6, 2008, during the seventh season of American Idol, the song was sung by contestant Syesha Mercado as the remaining top 4. After winning the 2008 United States presidential election, Barack Obama referred to the song, stating to his supporters in Chicago, "It's been a long time coming, but tonight, change has come to America." A duet of the song by Bettye LaVette and Jon Bon Jovi was included in We Are One: The Obama Inaugural Celebration at the Lincoln Memorial. In Washington DC, in the days leading up to the Inauguration of Barack Obama, this song could be heard played constantly in the city centre.

Sunday, February 20, 2011

Sunday With Nina :: Mississippi Goddam

In the 1960s, Nina Simone was part of the civil rights movement and later the black power movement. Her songs are considered by some as anthems of those movements, and their evolution shows the growing hopelessness that American racial problems would be solved.

Nina Simone wrote "Mississippi Goddam" after the bombing of a Baptist church in Alabama killed four children and after Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississipppi. This song, often sung in civil rights contexts, was not often played on radio. She introduced this song in performances as a show tune for a show that hadn't yet been written.

Other Nina Simone songs adopted by the civil rights movement as anthems included "Backlash Blues," "Old Jim Crow," "Four Women" and "To Be Young, Gifted and Black." The latter was composed in honor of her friend Lorraine Hansberry and became an anthem for the growing black power movement with its line, "Say it clear, say it loud, I am black and I am proud!"

With the growing women's movement, "Four Women" and her cover of Sinatra's "My Way" became feminist anthems as well.

But just a few years later, Nina Simone's friends Lorraine Hansberry and Langston Hughes were dead. Black heroes Martin Luther King, jr., and Malcolm X, were assassinated. In the late 1970s, a dispute with the Internal Revenue Service found Nina Simone accused of tax evasion; she lost her home to the IRS.

Nina Simone's growing bitterness over America's racism, her disputes with the record companies she called "pirates," her troubles with the IRS all led to her decision to leave the United States. She first moved to Barbados, and then, with the encouragement of Miriam Makeba and others, moved to Liberia.

A later move to Switzerland for the sake of her daughter's education was followed by a comeback attempt in London which failed when she put her faith in a sponsor who turned out to be a con man who robbed and beat her and abandoned her. She tried to commit suicide, but when that failed, found her faith in the future renewed. She built her career slowly, moving to Paris in 1978, having small successes.

In 1985, Nina Simone returned to the United States to record and perform, choosing to pursue fame in her native land. She focused on what would be popular, de-emphasizing her political views, and won growing acclaim. Her career soared when a British commercial for Chanel used her 1958 recording of "My Baby Just Cares for Me," which then became a hit in Europe.

Nina Simone moved back to Europe -- first to the Netherlands then to the South of France in 1991. She published her biography, I Put a Spell on You, and continued to record and perform.

There were several run-ins with the law in the 90s in France, as Nina Simone shot a rifle at rowdy neighbors and left the scene of an accident in which two motorcyclists were injured. She paid fines and was put on probation, and was required to seek psychological counseling.

In 1995, she won ownership of 52 of her master recordings in a San Francisco court, and in 94-95 she had what she described as "a very intense love affair" -- "it was like a volcano." In her last years, Nina Simone was sometimes seen in a wheelchair between performances. She died April 21, 2003, in her adopted homeland, France.

In a 1969 interview with Phyl Garland, Nina Simone said:

There's no other purpose, so far as I'm concerned, for us except to reflect the times, the situations around us and the things we're able to say through our art, the things that millions of people can't say. I think that's the function of an artist and, of course, those of us who are lucky leave a legacy so that when we're dead, we also live on. That's people like Billie Holiday and I hope that I will be that lucky, but meanwhile, the function, so far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times, whatever that might be.

Monday, February 14, 2011

Honoring My Father

1

AND IT CAME TO PASS in those days that Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin bunker. One week later, during the second week of May in the nineteen hundred and forty-fifth year, Nazi Germany surrendered unconditionally and the war in Europe ended.

In the first weeks of August, the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki and Hiroshima and the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria. On the fourteenth day of the month, Japan announced its surrender—so long as it could keep its emperor—and World War II, a most devastating war in terms of material destruction, global scale, and lives lost, ended.

Hazelle returned from the Philippines, where he had been stationed since the nineteen hundred and forty-second year, and found that the country he’d left behind wasn’t too kind to Negro servicemen returning from war.

Hazelle came back through California with a few of the others he’d attended Tuskegee with in the nineteen hundred and thirty-ninth year. After hanging out in the Arizona desert, he returned to Tennessee, to the city of Beale Street and barbeque, basement slow dances and jazz, three years before Elvis moved in from Tupelo, Mississippi.

Still, Hazelle couldn’t find work. And so it was on the fifteenth day of January in the nineteen hundred and forty-sixth year that he went up from Memphis, Tennessee, to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on a Greyhound bus. “Mighty nice day for a bus ride,” said Hazelle looking up at the driver from the curb. “What’s your name, sir?”

“Frankie,” the driver responded.

“My name is Hazelle, but you can call me Mister Charlie.” His tone was respectful with a hint of sarcasm. Hazelle tipped his hat to Frankie, flashed his gold tooth and moved to the back of the bus. And so he went up on a Greyhound Bus to the beer capital of America where his one-and-only brother Willie Lee said it was easier for a Negro man to find work.

2

Hazelle the second son was born by a midwife to Lee and Emma Ball Hickman in Inverness, Mississippi, sometime in the second month of the year.

Apparently, on the day he was born, no one glanced at the calendar. If someone had, they failed to record what day it was.

It wouldn’t become clear until the nineteen eighties exactly when Hazelle was born (and even then, his wife would ferociously debate the date or attempt to conceal the obvious), but throughout most of his life, Hazelle observed his birth on the twentieth day of February, in the nineteen hundred and twenty-fourth year.

Whenever he was born, one thing was clear without refute—Hazelle was jazz’s fraternal twin. Hazelle may not have been born in New Orleans, but he and jazz grew up together in the nineteen twenties, matured in the thirties, and took to the world in the forties. Hazelle claimed to have met Bessie Smith, heard Louis Armstrong play live, and auditioned for one of Billie Holiday’s back-up singers in Harlem—all before entering the service at the age of sixteen.

Believing himself sixteen-years-old in nineteen hundred and forty, he had to lie to gain entrance into the service, which only admitted young men of eighteen. Hazelle was blessed with a full head of gray hair at the ripe age of twelve (or sixteen, as the case may be). The service had no difficulty believing him to be nineteen.

3

And so it was that Hazelle entered the Army Air Force and concerned himself with the taking off and landing of airplanes. During the Second World War, he became a plotter. When he got to Milwaukee, Hazelle pursued his desire to work at a civilian airport.

Dressed up sharp, Army Air Force papers in hand, Hazelle took the long trolley ride from Sixth and Vine streets, where he lived with his brother, through the south side to General Mitchell Field, Milwaukee’s municipal airport.

He had called ahead for the interview, and over the phone, the hiring manager thought that Hazelle’s military plotting experience made him a very good candidate for the job of air traffic controller.

“Hazelle Hickman to see Mister Black about the plotter job.”

The eyes of the bifocaled receptionist with the fire-engine pompadour and pale, freckled skin scanned his tweed pants, his matching jacket, his rust and brown tie with the gold slanted stripes, his silver hair, and his colored skin and replied, “You can have a seat there and he’ll be right with you.”

Hazelle did what he was told, as he had for at least the last six years. Outside the window, he could see the two-engine prop planes rising and landing. Even though an emergency crash landing he’d endured during the war rendered him unwilling and unable to ever get inside those winged steel vessels again, airplanes would always deserve his wonder with their miraculous ability to defy the maw of gravity and take flight.

More than a dozen planes had come and gone while Hazelle waited patiently for Mister Black to be right with him. Finally, the pale-skinned woman emerged from behind a windowed door on the other side of the waiting area. “I’m so sorry that you’ve waited so long and that no one was able to call you before you came all this way. I’m so sorry, really I am. I wish I was able to help you, but the position was filled just today.” Her face flushed red as her mountain of hair. “You know what? Maybe I can help,” she continued, raising the pitch of her voice as though she’d made a remarkable discovery. “Consider this your lucky day. If you check downstairs in personnel, I know for a fact that there are several openings for second- and third-shift janitors.”

“Thank you, ma’am. You tell Mister Black there that I sure hope God blesses him.” He tipped his hat as he walked out the door. “You have yourself a real nice afternoon, ya hear?”

And so Hazelle became an interior decorator, a waiter, a cook, a chef, a house painter, and even pondered a career as a nightclub singer and a recording artist—oh, how that tenor voice could croon!—before he began his thirty-plus year tenure in office services at the Pabst Blue Ribbon Company. But before he met Pabst, he met the woman with whom he’d spend the rest of his life.

4

“I met her almost as soon as I got to Milwaukee. It was forty-six and I couldna been here for more than a month. I went to a USO dance at the Pfister Hotel. They had these events for veterans every so often. They were social gatherings where all the beautiful young ladies might come and give us handsome gentlemen a bit of their time and attention. It was one of the few events back in the day where black and white folk could mingle. They even had a big band. Live. You better believe couples were cuttin a rug, jitterbuggin all over the dance floor.

“I hadn’t yet picked out any beauties to test my toe and get my heart a-jumpin. Then my buddy, Smitty, stopped in the middle of our conversation and raised his eyebrows. He motioned for me to turn and look at the little bit of heaven standin just behind me with a smile on her face bright as a Mississippi morning. I walked right over to her.

“‘Well, hello sunshine,’ I kinda half sung in my best Nat King Cole impersonation. If a colored girl could blush, her face woulda glowed hot as the Arizona desert.

“I reached for her hand. ‘Before you try kissing it,’ she said, pulling her hand gently away from the path to my lips, ‘why don’t you take me on the dance floor and introduce yourself properly.’

“How can a man with a heartbeat resist that? They say it only happens in fairy tales. At the first sight of her, the very first sight, I knew it was love. So I guess you could say our fairy tale started on the dance floor that very night.”

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Sunday With Billie :: Strange Fruit

From Wikipedia:

"Strange Fruit" was a poem written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish high-school teacher from the Bronx, about the lynching of two black men. He published under the pen name Lewis Allan.[3][4]

In the poem, Meeropol expressed his horror at lynchings, possibly after having seen Lawrence Beitler's photograph of the 1930 lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana.

He published the poem in 1936 in The New York Teacher, a union magazine. Though Meeropol/Allan had often asked others (notably Earl Robinson) to set his poems to music, he set "Strange Fruit" to music himself. The piece gained a certain success as a protest song in and around New York. Meeropol, his wife, and black vocalist Laura Duncan performed it at Madison Square Garden.[5] (Meeropol and his wife later adopted Robert and Michael, sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were convicted of espionage and executed by the United States.)[6]

Barney Josephson, the founder of Cafe Society in Greenwich Village, New York's first integrated nightclub, heard the song and introduced it to Billie Holiday. Holiday first performed the song at Cafe Society in 1939. She said that singing it made her fearful of retaliation, but because its imagery reminded her of her father, she continued to sing it. She made the piece a regular part of her live performances.[7]

Holiday approached her recording label, Columbia, about the song, but the company feared reaction by record retailers in the South, as well as negative reaction from affiliates of its co-owned radio network, CBS.[8] Even John Hammond, Holiday's producer, refused. She turned to friend Milt Gabler, whose Commodore label produced alternative jazz. Holiday sang "Strange Fruit" for him a cappella, and moved him to tears. In 1939, Gabler worked out a special arrangement with Vocalion Records to record and distribute the song.[9] Columbia allowed Holiday a one-session release from her contract in order to record it.

She recorded two major sessions at Commodore, one in 1939 and one in 1944. "Strange Fruit" was highly regarded. In time, it became Holiday's biggest-selling record. Though the song became a staple of her live performances, Holiday's accompanist Bobby Tucker recalled that Holiday would break down every time after she sang it.[citation needed]

In her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, Holiday suggested that she, together with Lewis Allan, her accompanist Sonny White, and arranger Danny Mendelsohn, set the poem to music. The writers David Margolick and Hilton Als dismissed that claim in their work, Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song. They wrote that hers was "an account that may set a record for most misinformation per column inch". When challenged, Holiday—whose autobiography had been ghostwritten by William Dufty—claimed, "I ain't never read that book."[10]

(...)

Barney Josephson recognized the power of the song and insisted that Holiday close all her shows with it. When she was ready to begin it, waiters stopped serving, the lights in club were turned off, and a single pin spotlight illuminated Holiday on stage. During the musical introduction, Holiday would stand with her eyes closed, as if she were evoking a prayer. Numerous other singers have performed the work. In October 1939, Samuel Grafton of The New York Post described "Strange Fruit": "If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its 'Marseillaise'."

::

When I stumbled upon this website, I was floored.

Searching through America's past for the last 25 years, collector James Allen uncovered an extraordinary visual legacy: photographs and postcards taken as souvenirs at lynchings throughout America. With essays by Hilton Als, Leon Litwack, Congressman John Lewis and James Allen, these photographs have been published as a book "Without Sanctuary" by Twin Palms Publishers . Features will be added to this site over time and it will evolve into an educational tool. Please be aware before entering the site that much of the material is very disturbing. We welcome your comments and input through the forum section.Recently a close friend of mine who grew up in Maine, who had never heard of lynching, spontaneously burst into tears when I described this horror of our nation's past over lunch. The detail that seemed to get to him most were the postcards sent around inviting people to the well-attended lynching parties.

Experience the images as a flash movie with narrative comments by James Allen, or as a gallery of photos which will grow to over 100 photos in coming weeks. Participate in a forum about the images, and contact us if you know of other similar postcards and photographs.

I recommend viewing the flash movie option above. The commentary elicits chills.

![[lynching.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi6lVxHz_v4GuzsRKSYZpvkz5vkVK_RiCohh-QDr4RqGFYe9F9YZEtM7N_b4zwR7IFfvAqmH-glyOjIXo_p1gLPzhiGtg2hihzVIC1VCiwwhAf_Ydx4LldHuoNwX0Z-P5ChWCBi4Q/s1600/lynching.jpg)

Wednesday, February 09, 2011

Put Your Foot In It: The Culinary Reach Of The African Diaspora

Okra from my farm in Maine.

In the final chapter of High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America (Bloomsbury, Jan. 4), Jessica B. Harris looks at the culinary cosmos leavened by the narratives of the African diaspora. The Bryn Mawr alum, a tenured professor at Queens College who holds a Ph.D. from NYU, beckons the reader into a sacred, long-loved cookery where iron pots of gumbo and the aromas of praline and molasses speak to the centuries, continents and cultures traversed by African-Americans.

Harris, the author of 11 cookbooks, uses her latest to follow the foodways of the diaspora, from the West African vendors selling pepperpot on the streets of Philadelphia to the chuckwagon cooks in the Westward migration. Throughout, Harris traces the story of African-American chefs who found cooking as a means of expression and social mobility. Harris will read from High on the Hog at the Free Library Feb. 1.

City Paper: Why write this more historically based book instead of another cookbook?

Jessica B. Harris: I thought it was time to start the dialogue about the history of this food, and the history of its people as seen through the food. We live in a world of cookbooks — Lord knows, I've contributed 11 to that world — but this is just a deeper, perhaps more thoughtful, study of it.

CP: In High on the Hog, you go back to dishes that were popular in the 18th century, many of which we don't see in the same form anymore. Has this influenced how you cook?

JH: Actually, no. I cook the same way as always. There's food that I research and there's food that I eat every night for dinner. In some cases, I will cook traditional African-American dishes for celebrations or traditional dishes from the diaspora.

CP: Have we lost some of this traditional food in our culture?

JH: Not that much has been lost, actually. People eat okra, people eat sesame, people eat watermelon. All of these are ingredients that came from the African continent. Much of what we eat on a daily basis is food and foodstuff that comes from Africa. We just are largely unaware that they do. ... Did you have a cup of coffee this morning?

CP: Yes, several.

JH: In fact and indeed, coffee originated in the Ethiopian Highlands. That's what I mean. Most of us don't know that.

Read the rest....

I didn't know it. Learn something new everyday.

Sunday, February 06, 2011

Sunday With Paul :: Nobody Knows The Trouble I've Seen

Introduction

Paul Robeson, a great American singer and actor, spent much of his life actively agitating for equality and fair treatment for all of America's citizens as well as citizens of the world. Robeson brought to his audiences not only a melodious baritone voice and a grand presence, but magnificent performances on stage and screen. Although his outspokenness often caused him difficulties in his career and personal life, he unswervingly pursued and supported issues that only someone in his position could effect on a grand scale. His career flourished in the 1940s as he performed in America and numerous countries around the world. He was one of the most celebrated persons of his time.

Narrative Essay

Paul Leroy Robeson was born in Princeton, New Jersey, on April 9, 1898, the fifth and last child of Maria Louisa Bustill and William Drew Robeson. During these early years the Robeson's experienced both family and financial losses. At the age of six Paul and his siblings, William, Reeve, Ben and Marian suffered the death of their mother in a household fire. This was followed a few years later with their father's loss of his Princeton pastorate. After moving first to Westfield, the family finally settled in Somerville, New Jersey, in 1909, where William Robeson was appointed pastor of St. Thomas AME Zion Church.

Enrolling in Somerville High School, one of only two blacks, Paul Robeson excelled academically while successfully competing in debate, oratorical contests, and showing great promise as a football player. He also got his first taste of acting in the title role of Shakespeare's Othello. In his senior year he not only graduated with honors, but placed first in a competitive examination for scholarships to enter Rutgers University. Although his other male siblings chose all-black colleges, Robeson took the challenge of attending Rutgers, a majority white institution in 1915.

In college between 1915 to 1919, Robeson experienced both fame and racism. In trying out for the varsity football team, where blacks were not wanted, he encountered physical brutality. In spite of this resistance, Robeson not only earned a place on the team but was named first on the roster for the All-American college team. He graduated with 15 letters in sports. Academically he was equally successful, elected a member of the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa Society and the Cap and Skull Honor Society of Rutgers. Graduating in 1919 with the highest grade point average in his class, Robeson gave the class oration at the 153d Rutgers Commencement.

With college life behind him, Robeson moved to the Harlem section of New York City to attend law school, first at New York University, later transferring to Columbia University. He sang in the chorus of the musical Shuffle Along (1921) by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, and made his acting debut in 1920 playing the lead role in Simon the Cyrenian by poet Ridgely Torrence. Robeson's performance was so well received that he was congratulated not only by the Harlem YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) audience but also by members of the Provincetown Players who were in the audience. While working odd jobs and taking part in professional football to earn his college fees, Robeson met Eslanda "Essie" Cardozo Goode. The granddaughter of Francis L. Cardozo, the secretary of state of South Carolina during Reconstruction, she was a graduate of Columbia University and employed as a histological chemist. She was the first black staff person at Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. The couple married on August 17, 1921, and their son Paul Jr. was born on November 2, 1927.

To support his family while studying at Columbia Law School, Robeson played professional football for the Akron Pros (1920--1921) and the Milwaukee Badgers (1921--1922), and during the summer of 1922 he went to England to appear in a production of Taboo, which was renamed Voodoo. Once graduating from Columbia in 1923, Robeson sought work in his new profession, all the while singing at the famed Cotton Club in Harlem. Offered an acting role in 1923 in Eugene O'Neill's All God's Chillun Got Wings, Robeson quickly took this opportunity; he had recently quit a law firm because the secretary refused to take dictation from a black person.

Although All God's Chillun brought threats by the Ku Klux Klan because of the play's interracial subject matter and the fact that a white woman was to kiss Robeson's hand, it was an immediate success. It was followed in 1924 by his performances in a revival of The Emperor Jones, the play Rosanne, and the silent movie Body and Soul for Oscar Micheaux, an independent black film maker. In 1925 Robeson debuted in a formal concert at the Provincetown Playhouse. His performance which consisted of Negro spirituals and folk songs was so brilliant that he and his accompanist, Lawrence Brown, were offered a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company. Encouraged by this success, Robeson and Brown embarked on a tour of their own, but were sorely disappointed. Even though they received good reviews, the crowds were small and they made very little money. What Robeson came to know was that his talents in acting and singing would serve as the combined focus of his career.

Acting and Singing Career

Robeson's acting career started to take off in 1928 when he accepted the role of Joe in a London production of Show Boat by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein. It was his singing of "Ol' Man River" that received the most acclaim regarding the show and earned him a great degree of attention from British socialites. Robeson gave concerts in London at Albert Hall and Sunday afternoon concerts at Drury Lane. In spite of all this attention, Robeson still had to deal with racism. In 1929 he was refused admission to a London hotel. Because of the protest raised by Robeson, major hotels in London said they would no longer refuse service to blacks.

Much attention was given to Robeson's acting and singing and he was embraced by the media. The New Yorker magazine in an article by Mildred Gilman referred to Robeson as "the promise of his race," "King of Harlem," and "Idol of his people." Robeson returned briefly to America in 1929 to perform at a packed Carnegie Hall. In May of 1930, after establishing a permanent residence in England, Robeson accepted the lead role in Shakespeare's Othello. This London production at the Savoy Theatre was the first time since the performance of the great black actor Ira Aldridge in 1860 that a major production company cast a black man in the part of the Moor. Robeson was a tall, strikingly handsome man with a deep, rich, baritone voice and a shy, almost boyish manner. The audience was so mesmerized by his performance in Othello that the production had 20 curtain calls.

Accolades for outstanding acting and singing performances were prevalent during the 1930s in Robeson's career, but his personal and home life were surrounded by difficulties. His wife Eslanda "Essie," who had published a book on Robeson, Paul Robeson, Negro (1930), sued for divorce in 1932. Her actions were encouraged by the fact that Robeson had fallen in love and planned to marry Yolande Jackson, a white Englishwoman. Jackson, whom Robeson called the love of his life, had originally accepted his proposal but later called the marriage off. It was thought by some who knew the Jackson family well that she was strongly influenced by her father, Tiger Jackson, who was less than tolerant of Robeson and people of color in general. With his marriage plans cancelled, Robeson and his wife came to an understanding regarding their relationship, and the divorce proceedings were cancelled.

Activism

Robeson returned to New York briefly in 1933 to star in the film version of Emperor Jones before turning his attention to the study of singing and languages. His stay in the United States was a short one due to his treatment by the racist American film industries and because of criticism by blacks regarding his role as a corrupt emperor. Upon returning to England, Robeson eagerly immersed himself in his studies and mastered several languages. Robeson along with Essie became an honorary members of the West African Students' Union, becoming acquainted with African students Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, future presidents of Ghana and Kenya, respectively. It is also during this time that Robeson played at a benefit for Jewish refugees which marked the beginning of his political awareness and activism.

Robeson's inclination to aid the less fortunate and the oppressed in their fight for freedom and equality was firmly rooted in his own family history. His father William Drew Robeson was an escaped slave who eventually graduated from Lincoln College in 1878, and his maternal grandfather, Cyrus Bustill, was a slave who was freed by his second owner in 1769 and went on to become an active member of the African Free Society. Recognizing the heritage that brought him so many opportunities, Robeson, between 1934 and 1937 performed in several films that presented blacks in other than stereotypical ways. He acted in such films as Sanders of the River (1935), King Solomon's Mines (1937) and Song of Freedom (1937).

On a trip to the Soviet Union in 1934 to discuss the making of the film Black Majesty, Robeson not only had discussions with the Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein during his trip but was so impressed regarding the education against racism for schoolchildren that he began to study Marxism and Socialist systems in the Soviet Union. He also decided to send his son, nine-year-old Paul Jr., to school in the Soviet Union so that he would not have to contend with the racism and discrimination Robeson confronted in both Europe and America.

Robeson continued acting in films confronting stereotypes of blacks while receiving rave reviews for his success in singing "Ol' Man River" in the 1936 film production of Show Boat. He also embarked on a more active role in fighting the injustices he found throughout the world. Robeson co-founded the Council on African Affairs to aid in African liberation, sang and spoke at benefit concerts for Basque refugees, supported the Spanish Republican cause, and sang at rallies to support a democratic Spain along with numerous other causes. At a benefit in Albert Hall in London, Robeson is quoted in Philip Foner's Paul Robeson Speaks as saying "The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative." This statement echoed a clear and focused direction of Robeson's personal and professional life.

In 1939 Robeson stated his intentions to retire from commercial entertainment and returned to America. He gave his first recital in the United States at Mother AME Zion Church Harlem where his brother Benjamin was pastor. Later on in the same year Robeson premiered the patriotic song "Ballad for Americans" on CBS radio as a preview of a play by the same name. The song was so well received that studio audiences cheered for 20 minutes after the performance while the listening audience exceeded the response even for Orson Welles's famous Martian scare program. Robeson's popularity in the United states soared and he remained the most celebrated person in the country well into the 1940s. He was awarded the esteemed NAACP Spingarn Medal (1945) as well as numerous other awards and recognitions from civic and professional groups. In the American production of Othello (1943), Robeson's performance placed him among the ranks of great Shakespearean actors. The production ran for 296 performances--over ten months--and toured both the United States and Canada.

Robeson's political commitments became foremost in his life as he championed causes from South African famine relief to support of an anti-lynching law; in September 1946 he was among the delegation that spoke with President Harry S Truman about anti-lynching legislation. The meeting was a stormy one as Robeson adamantly urged Truman to act, all the while defending the Soviet Union and denouncing United States' allies. In October of the same year when called before the California Legislative Committee on Un-American activities, Robeson declared himself not a member of the Communist Party but praised their fight for equality and democracy. This attempt at branding him as un-American was successful in causing many to distrust his political commitments. Regardless of these events, Robeson decided to retire from concert work and devote himself to gatherings that promoted the causes to which he had dedicated himself.

In 1949 Robeson embarked on a European tour and in doing so spoke out against the discrimination and injustices that blacks in American had to confront. His statements were distorted as they were dispatched back to the United States. Although Robeson got mixed responses from the black community, the backlash from whites culminated in riot before a scheduled concert in Peekskill, New York, on August 27, 1949; a demonstration by veteran organizations turned into a full-blown riot. Robeson was advised of this and returned to New York. He did agree to do a second concert on September 4 in Peekskill for the people who truly wanted to hear him. The concert did take place but afterwards a riot broke out which lasted into the night leaving over 140 persons seriously injured. With such violence surrounding Robeson's concerts, many groups and sponsors no longer supported him.

By 1950 Robeson had received by so much negative press that he made plans for a European tour. His plans were abruptly halted because the United States government refused to allow him to travel unless he agreed not to make any speeches. With no passport and denied his freedom of speech abroad, Robeson continued to speak out in public forums and through his own monthly newspaper, Freedom. Barred from all other forms of media, his own newspaper became his primary platform from 1950 to 1955. His remaining supporters encompassed the National Negro Labor Council, Council on African Affairs, and the Civil Rights Congress. The NAACP openly attacked Robeson while other black organization shunned him in fear of reprisals. Undaunted by these negative responses, Robeson traveled the United States encouraging groups to fight for their rights and for equal treatment. Even though he suffered from health as well as financial difficulties, Robeson held firm to his convictions and published in 1958 his autobiography Here I Stand through a London publishing house.

On May 10, 1958, Robeson gave his first New York concert in ten years to a packed Carnegie Hall. When the concert was over, he informed the audience that the passport battle had been won. From 1958 to 1963 Robeson traveled to England, the Soviet Union, Austria, and New Zealand. He was showered with awards and played to packed houses throughout his travels. After being hospitalized several times throughout his trip due to a disease of the circulatory system, Robeson returned to the United States. Much had changed since the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and school integration were in full enactment. Robeson was welcomed on his return by Freedomways, a quarterly review which saw him as a powerful fighter for freedom. A salute to Robeson was given in 1965 which was chaired by actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee along with writer James Baldwin and many other admirers.

Eslanda "Essie" Robeson died of cancer in 1965 at the age of 68 and Robeson went to live with his sister Marian in Philadelphia. He remained in seclusion until he died there on January 23, 1976; on his 75th birthday four days later a "Salute to Paul Robeson" was held in Carnegie Hall. Paul Leroy Robeson's funeral was held at Mother AME Zion Church in Harlem before a crowd of 5,000.

On February 24, 1998, Robeson received a posthumous Grammy lifetime achievement award. His honors are numerous, as Robeson's life is being depicted through exhibits, film festivals, and lectures. Upon the centennial of his birth on April 9, 1998, at least 25 U.S. states and several countries worldwide hosted celebrations of his life and work in every conceivable manner.

Paul Robeson was truly a man who saw a commitment to the oppressed, and particularly black people, as a much more profound calling than the accolades he received for his astonishing talents. His extraordinary voice and engaging acting abilities would have undoubtedly brought him more fame, fortune, and approval than the activist role he pursed instead. It is because of this clear vision of justice that he is remembered as a great American and a great citizen of the world.

Sources

Duberman, Martin B. Paul Robeson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988.

Foner, Philip S. Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews 1918--1974. New York: Brunner/Mazel Publishers, 1978.

Jackson, Kenneth T., and others, eds. Dictionary of American Biography. Supplement Ten, 1976--1980. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1995.

"Robeson Receives Posthumous Grammy." New York Times, February 25, 1998.

Southern, Eileen. Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Williams, Michael W., ed. The African American Encyclopedia. New York: Marshall Cavendish, 1993.Collections

Paul Robeson's papers are in the Robeson Family Archives, Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington D.C.

![[lynching2.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh07cl1uWqk-LrH0uqMqvMTXA-mC29Ag9DQkW8Iwld8GpaIL8IIQyuYh6R0Khp8Y6Tfdmr3IpatOzuR4DNKFpV-U5_pRuqfnz-jyXpwTcqgCu5yDx1qswD9KxB4a3upPQ_FScHDdQ/s1600/lynching2.jpg)