Prolific gay composer Billy Strayhorn—who penned music for Nat King Cole and Duke Ellington—finally gets his due in a new documentary and CD.

Prolific gay composer Billy Strayhorn—who penned music for Nat King Cole and Duke Ellington—finally gets his due in a new documentary and CD.

by Kurt B. Reighley

from The Advocate

The new documentary Billy Strayhorn: Lush Life tells the story of a great love between two men. But it isn’t a romance, and only the titular protagonist is gay.

Billy Strayhorn wrote or cowrote several of the 20th century’s greatest jazz and pop songs: “Satin Doll,” “Lotus Blossom,” “Something to Live For.” He penned his masterpiece, “Lush Life,” recorded by everyone from Nat King Cole to Rickie Lee Jones, at the age of 16.

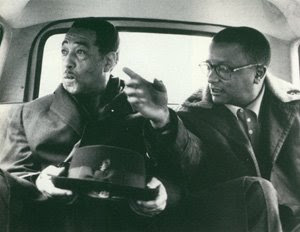

These gems have become Strayhorn’s legacy. But in his lifetime—which began in Dayton, Ohio, in 1915 and ended in a New York hospital 52 years later—the composer, arranger, and pianist was best known as Duke Ellington’s right hand. As Lush Life illuminates, the two enjoyed a complex relationship, which at times hindered Strayhorn from becoming a star in his own right but also permitted him freedom he might otherwise never have enjoyed.

Continue reading “He wrote the songs”

Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn

I READ THIS marvelous book back when it first came out in hardcover in 1996. Now that a new documentary and CD are coming out, I’ll want to reread it. There was something about Strayhorn’s story that I identified with. I remember crying a lot as I read it. Perhaps it was that he seemed an orphan of sorts, adopted into Duke Ellington’s music family. I had just started to search for my birth relatives, so I was an open wound.

Whatever the connection to Strayhorn I felt, I was simply moved by David Hadju’s elegiac narrative about the great man behind music’s greatest man.

At the time, there was buzz that a feature film based on the book was going to be made about Billy Strayhorn, played by Will Smith, who had just received raves for his turn in Six Degrees of Separation. Needless to say, nothing came of that.

Instead of waiting for my review of the book, which I may or may not get around to writing, I decided to post the following one that I found while surfing the net for artwork to include in this entry.

Instead of waiting for my review of the book, which I may or may not get around to writing, I decided to post the following one that I found while surfing the net for artwork to include in this entry.Duke’s alter ego

by Richard Williams

Jazz has produced several memorable threnodies - one thinks of John Lewis’s lament for Django Reinhardt or Charles Mingus’s salute to Lester Young - but none more affecting than Blood Count, recorded by the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1967, a few months after the death of Billy Strayhorn, Ellington’s long-time collaborator.Continue reading the book review

Dyed in the deepest indigo, it features the exquisitely mournful alto saxophone of Johnny Hodges, for whom Strayhorn had fashioned many wonderful settings. What makes Blood Count unusual is that Strayhorn wrote the piece himself. In fact, it was the last thing he composed, its title a rueful reflection of his plight in the final stages of a losing battle against cancer.

The partnership between Ellington and Strayhorn, who wrote together between 1940 and 1967, constitutes a mysterious phenomenon which went almost unexamined and hence largely misunderstood during the lifetimes of its principals.

As one of the great instruments of jazz, the Ellington orchestra was widely assumed to be the vehicle for its leader’s genius. Yet it was Strayhorn who produced some of the orchestra’s best known pieces of the post-1940 era: “Chelsea Bridge”, “Passion Flower”, “Day Dream”, and “Take the A Train”, that irresistibly hectic evocation of the now-demolished elevated railroad running from 59th to 125th Streets, adopted by Ellington as his signature tune and therefore assumed by many fans to have been written by the leader.

As David Hajdu demonstrates in this expert and enjoyable biography, Strayhorn also contributed in a less clearly identifiable way to such major items of Ellingtonia as the extended works titled “Black, Brown and Beige”, “Such Sweet Thunder” and “Suite Thursday”. He was often employed in completing or revising Ellington’s own sketches, and frequently his participation went uncredited.

If the rest of the world thought about Strayhorn at all during his years with Ellington, it probably conceived him as a shy fellow who preferred to stay at home and toil in obscurity while Ellington took the band around the world on one long party. Not the least of Hajdu’s discoveries is that something like the opposite was the case.

2 comments:

And he was only 16 when he wrote Lush Life, one of my favourite songs.

An amazing song, music and lyrics, for someone so young, no?

Post a Comment